Cherry Blossom Season

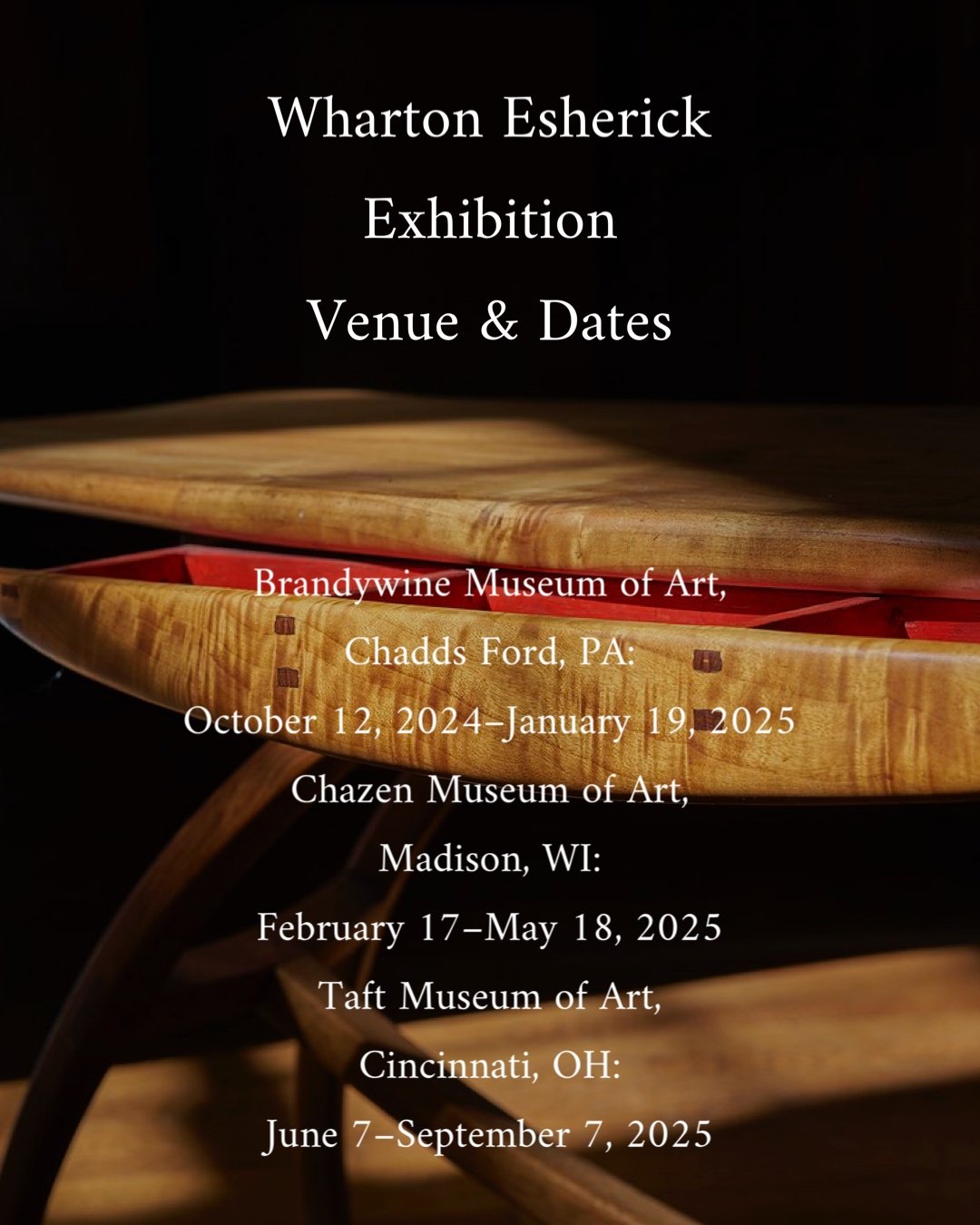

Cherry Blossom season with pieces by woodworkers Dick Cruger, George Nakashima and Wharton Esherick

A Goldfinch Enjoying the Japanese Cherry Blossoms

Cherry Blossoms are symbolic of beauty, vitality, honor, hope and peace.

Works in Cherry Wood by Dick Cruger, Wharton Esherick and George Nakashima

Wishing All a Bright HOLIDAY Season and A Momentous 2023

Wishing all a bright HOLIDAY season and a momentous 2023

Photography by PFFK#7

Harry Bertoia. Who Was He?

Harry Bertoia. Who was he?

“The urge for good design is the same as the urge to go on living”

-Harry Bertoia

Born March 10, 1915

In an Italian rural village, populated by approximately 500 people, where

Julius Caeser often traveled, and where church bells chime announcing every wedding and birth.

Harry Bertoia mentioned his love for Italy, the sun, gardens, grapevines, people laughing, drawing and creating. Many we may love

as well however, Harry’s intellect and artistic ability created works which live on through his students, sculpture, design and sound.

A stable in San Lorenzo, the Italian village of his childhood, still houses small wooden toys and wire formed baskets hang

Harry made as a child.

Bracelet made from one continuous strand of coiled copper with only a single welded point.

Harry later gifted to his daughter-in-law in 1977

A limited edition series was within possibility for Norway gallery

Kaare Berntsen, Bertoia passed before the series materialized

Exhibited

Baum School of Art 2001

Allentown, PA

Early on he showed a talent for precision with metal, drawing and model making. At the age of 15, he was faced with staying in Italy or venturing to America to seek formal art training. Without speaking English, Harry moved to Detroit in 1930 where his older brother was living and working in the Ford Factory. In 1935 Harry was accepted into Cass Technical High School and he began the 3 hour round trip bus ride to attend the preparatory school for arts and science. He graduated from Cass in 1936 with numerous awards and was widely known as the most gifted art student they had ever had. After graduation, a teacher named Miss Louise Greene drove Harry — along with his portfolio and a small box of jewelry — to interview with Eliel Saarinen, President of Cranbrook Academy of Art, who offered Harry a scholarship on the spot.

After excelling as a student, Eliel Saarinen asked Harry to reopen the metal shop. Harry accepted and worked as the metal smith instructor while continuing as a student.

Harry’s jewelry works have been in continuous exhibitions from MOMA’s 1946 Modern Handmade Jewelry to being in permanent collections of Dallas Museum of Art, Cranbrook Academy of Art and LACMA.

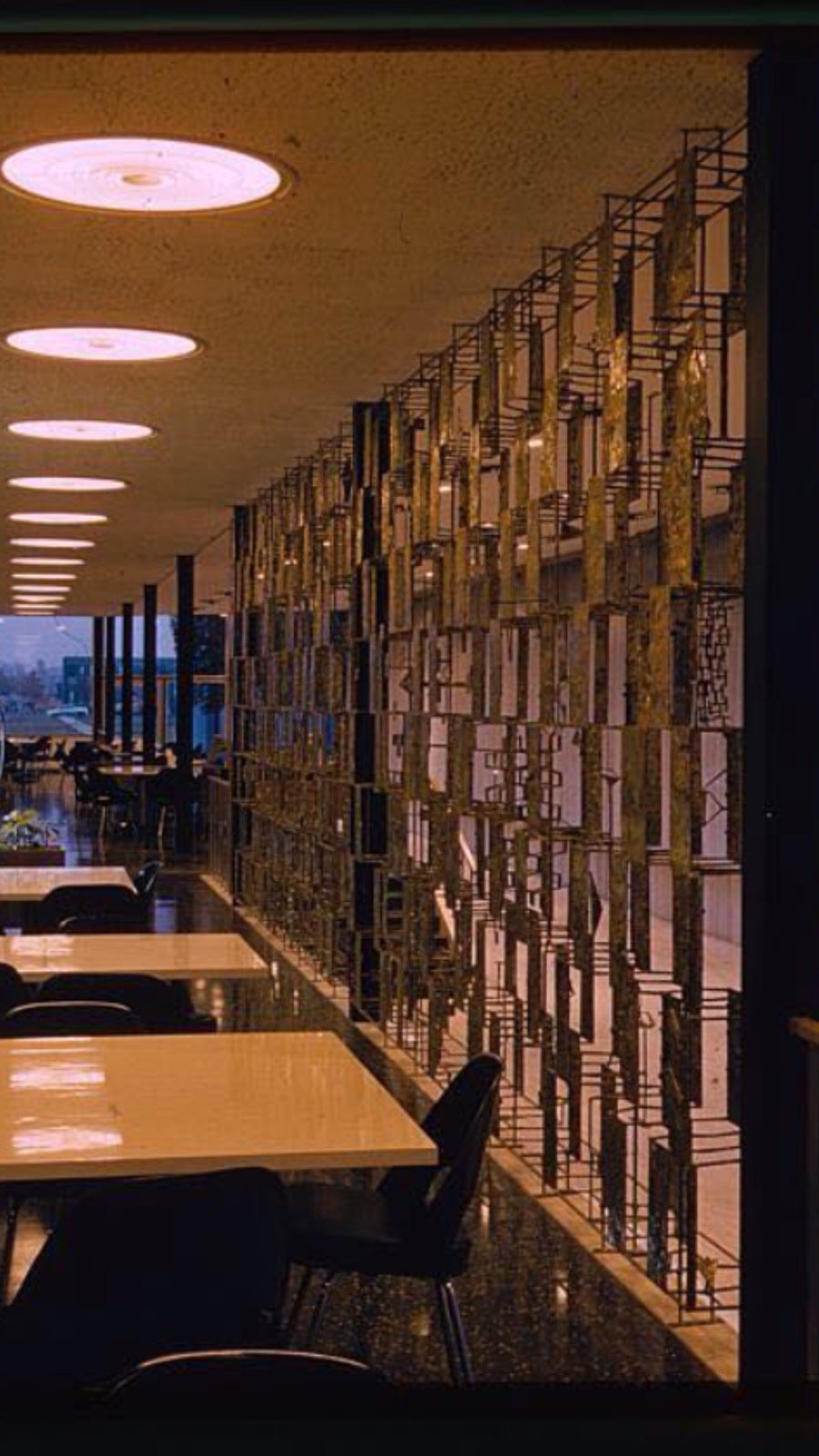

Metal Block Screen Sculpture circa 1950s, as viewed from the top

““I am rather silent, resolute and industrious. I respect and admire persons of probity and morality, moderation and temperance. I can use any tool or machinery with dexterity… I like to see good plays and enjoy taking an active part outdoors…. I am interested in some branches of science, namely biology, sociology, astronomy and geology.””

After marrying Brigitta, and working with the Eames couple in California, Harry moved his family to Pennsylvania in 1950. He began work with Hans and Florence Knoll. Florence, born in Saginaw, Michigan, was orphaned and practically adopted by the Saarinens when she attended Cranbrook. While there, she also met Harry.

In 1951 the Bertoias settled along Aquetong Road in New Hope, Pennsylvania where they became friends with master woodworker George Nakashima and his family. Harry and George shared many philosophies including much of American craftsmanship, as well as a general disdain for plastic and mass production. The two would exchange works, and Harry’s sculptures remain on the George Nakashima Woodworkers estate outside the Chair Shop and in the Conoid Studio. A carved walnut stool by George became Harry’s welding stool.

Today, George’s daughter Mira continues George Nakashima Woodworkers , while Harry’s daughter Celia helms the Harry Bertoia Foundation.

Celia’s book The Life and Work of Harry Bertoia is the main source for the background details presented here.

Standing Panel Multi-plane Sculptures

Beginning in 1952, Knoll showrooms throughout the US featured Bertoia’s standing panels with his Diamond and Bird Chair designs manufactured and sold through

Knoll Associates

Panel in the General Motos Technical Center

Warren, Michigan

Architect Eero Saarinen began the design for GM through Harley Earl in 1945 and commissioned Harry for a large panel, which was completed in 1953.

The opening ceremony of the 710 acre GM Technical Center in 1956 was deemed the “Versailles of Industry” by Life Magazine and live broadcasted by NBC

The screen was Harry’s first sculptural commission and measured

10’ x 36’ x 8”

In 2014, GM Techinal Center was designated a

National Historic Landmark

Large scale commissions continued from Manufactures Hanover Trust (later Chase Bank), on Fifth Avenue in New York City, for a large screen in the

Gordon Bunshaft designed building. Other commissions came in from MIT, Dallas Public Library, St John’s Unitarian Universalist Church,

Eastman Kodak, Federal Reserve Bank and Dulles International Airport.

Harry Bertoia Foundation provides an interactive timeline of his public works visit here.

Bush Form with only known red flower bud forging circa 1973

A conversation with Celia Bertoia:

”Harry once said something like I'm almost sad to see a flower at its peak, knowing that it will fade in a few days”

Harry Bertoia Bush Form exhibited with a sculpture by Carl Milles. Milles was a friend of the Bertoias and attended Harry and Brigitta’s wedding. Millesgårdens

Exhibited 2021

Cranbrook Museum of Art

With Eyes Opened: Cranbrook Academy of Art Since 1932

Bertoia’s welded works of nature came in bush forms, dandelions, weeping willows, hay bundles and wheat. The series of sculptures began in the 1960s and became a point of contention when galleries began vying to be the exclusive representative of his works. The forms continues to gain in popularity as collectors discover Harry and his complex welded metals sculpted into nature’s growings.

Sonambient

”the sound environment created by the tonal sculpture"

”the ambiance of the atmosphere which resulted from the sounding sculptures, once touched”

In partnership with John Brien and Celia Bertoia, Third Man Pressing, located in Detroit and founded by Jack White, released Harry Bertoia’s complete Sonambient LP collection in 2021

The set features Bertoia’s 11 original Sonambient Barn recordings remastered on 11 discs with an 80 page book detailing the history and an interview with the

Smithsonian and Harry Bertoia

The Sonambient Barn was completed in 1969 after remodeling the 200 year old barn on the Bertoia estate in Pennsylvania. Original oak beams remained as the ceiling and vertical windows were added to allow sunlight. In that space, Harry worked with the tonal sculptures knowing which metals created certain sound.

The sculptures varied in height from a few inches to twenty feet tall. They were the longest continual running of his works spanning from

1960 to 1978.

Bertoia was the first artist to join sound with sculpture in America. Influenced from sounds of his childhood, certain tones reminded him of the church bells chiming in San Lorenzo from his childhood. His welded sculptures demonstrated his understanding of vibrations through metal like nature’s wind through reeds.

Listen here

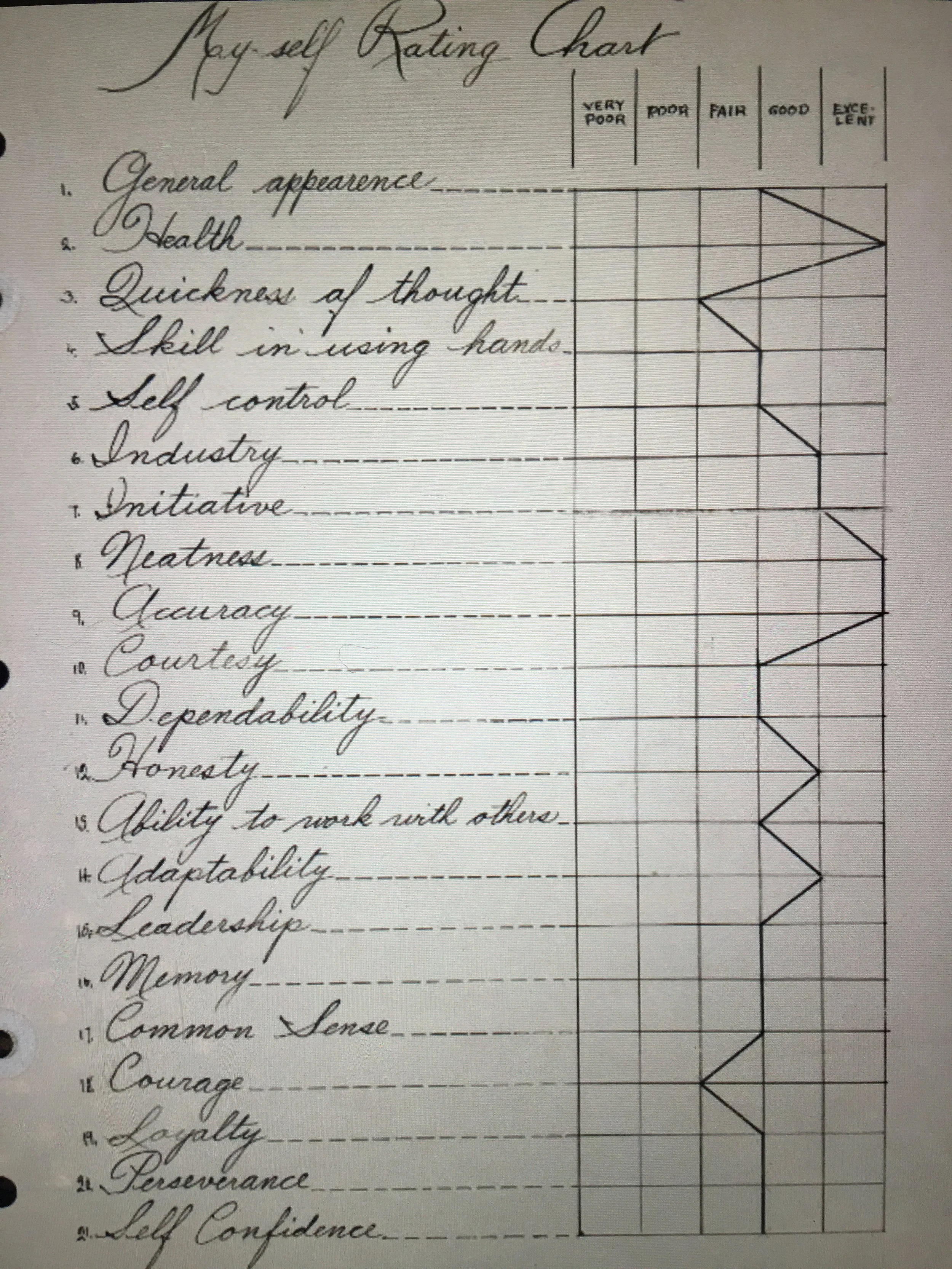

Harry Bertoia Self Rating

In other words:

Healthy, neat, accurate, honest, adaptable, etc., need to work on some courage; as for quickness of thought, well, when your mind is filled with so many ideas. . .

Harry Bertoia

Sculpting Mid-Century Modern Life

January 29, 2022 - April 24, 2022

Over 100 of Bertoia’s works in metal, monotypes,

furniture design, jewelry, and sculptures brought together in a retrospective of the artist by Nasher Sculpture Center

Chief Curator Jed Morse and independent curator Dr. Marin Sullivan

Harry’s daughter Celia opening evening of Harry Bertoia Sculpting Mid-Century Modern Life

Nasher Sculpture Center Dallas, Texas

January 2022

Image courtesy of Harry Bertoia Foundation

Unless otherwise noted, all photography created by, and copyright of, Pipe Full o’ Fun Kit #7

Sources

Celia Bertoia

The Life and Work of HARRY BERTOIA The Man . The Artist . The Visionary by Celia Bertoia

Harry Bertoia Foundation

Cranbrook Academy of Art

Instagram

Smithsonian

Third Man Pressing

YouTube

View our images of Harry Bertoia artworks below on Instagram or throughout TEI here

Merriest of Holidays and Happy New Year!

Wrapping our year and wishing all a bright 2022 from our locations in Detroit, Sweden and Texas. Deep in the heart of each you’ll see our appreciation for historic architecture, culture and nature. With more to come in 2022 and much to do!

Wishing you a bright New Year!

From Detroit, Texas and Sweden

Detroit

Sweden

Texas

Harry Bertoia and Paul Evans

Harry Bertoia and Paul Evans Masterworks now on exhibit:

Cranbrook Museum of Art With Eyes Opened

Now on exhibit Cranbrook Museum of Art

With Eyes Opened Cranbrook Academy of Art Since 1932

Two Masterworks by Harry Bertoia and Paul Evans from the TEI Collection

June 18, 2021 - September 19, 2021

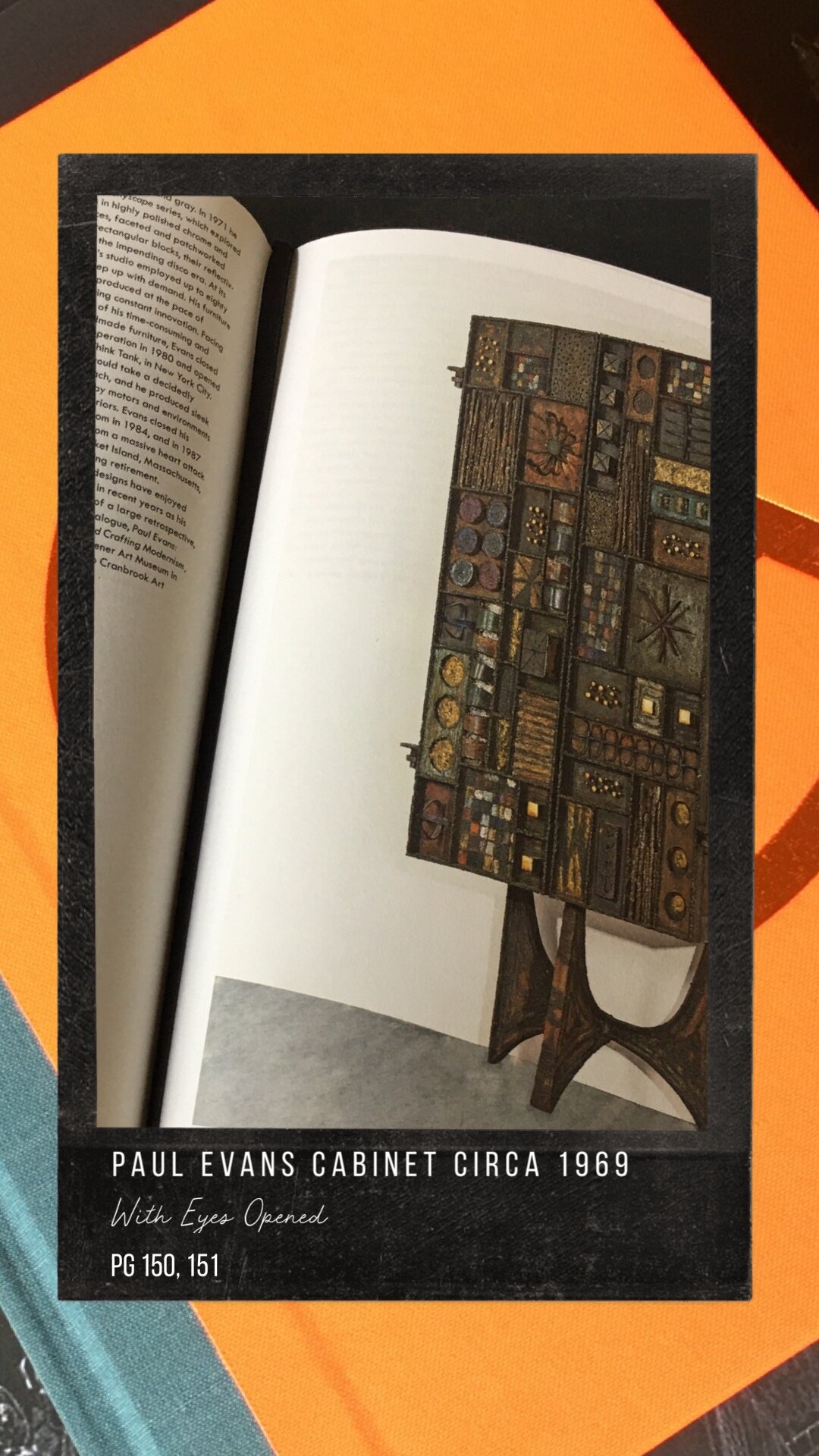

One of a Kind Paul Evans Sculpted Front Cabinet circa 1969

Paul Evans attended Cranbrook in Fall 1952 with a focus on metal-smithing.

While Art Instructor Richard Thomas commented

"Excellent mechanically. Experimental attitude seriously limited. Over confident, decidedly intolerant and selfish. Devious. I would hesitate to recommend him for a situation requiring close cooperation with others."

Evans went on to be considered the father of the modern art furniture movement.

Each of his sculpture front works were custom and took 3 to 6 months, less than 75 examples were made.

“To me the Sculpture Front is the signature piece by Paul Evans. We would go through periods where we would be focused on Sculpture Front. Then we would move to groups of sculpture, other pieces. But we always came back to the Sculpture Front.”

~Dorsey Reading

Thomas quote source: Paul Evans at The Michener Constance Kimmerle Lecture

Paul Evans Laser Etching on Plex and Scale Model from Soirée by Dick Cruger

Rendering by PFFK7 for The Exchange Int

With Eyes Opened: Cranbrook Academy of Art Since 1932

Surveys the history of the Cranbrook Academy of Art since its official founding in 1932.

Curated by Andrew Brauvelt more than 250 works from 220 plus alumni represent the various programs of study at the school–architecture, ceramics, design, fiber, metals, painting, photography, printmaking, and sculpture are exhibited occupying all of the museum’s galleries.

Harry Bertoia Bush Form circa 1973

Harry Bertoia emigrated to Detroit at the age of 11 from Italy. After attending Cass Technical High School he was awarded a full scholarship to Cranbrook Academy of Arts in 1937.

She said “Oh, no, you go there, you’ll be happy.”

”So I trusted her completely and it certainly turned out that my stay at Cranbrook actually was so important that I feel it was one of the basic periods of my life where things began to really change and happen.”

Harry Bertoia referencing Miss Greene’s recommendation to Cranbrook

Source: The Life and Work of Harry Bertoia by Celia Bertoia

In conversation with

Harry’s daughter Celia around the rarity of the

only red forging known in

Bertoia’s works

Harry once said something like I'm almost sad to see a flower at its peak, knowing that it will fade in a few days

Archival sketch courtesy of

Harry Bertoia Foundation

Harry Bertoia Laser Etching on Plex and Scale Model from Soirée by Dick Cruger

Rendering by PFFK7 for The Exchange Int

Masterworks by Paul Evans and Harry Bertoia are located in the Main Gallery

Proudly on loan from The Exchange Int and The S. pace Detroit

—

Not far from Detroit, America’s only city to be awarded UNESCO’s City of Design, is Cranbrook Academy of Art and Cranbrook Art Museum. The 319 acre campus was founded in 1904 by Detroit philanthropists George Gough Booth and Ellen Scripps Booth. The grounds feature the work of world-renowned architects and sculptors such as Eliel Saarinen, Albert Kahn, Carl Milles, Steven Holl, Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, Rafael Moneo, Peter Rose, and Marshall Fredericks. Along with Harry Bertoia and Paul Evans other Midcentury Modernism icons included in the exhibit are Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, Ruth Adler Schnee, Florence Knoll and Olga de Amaral.

Above: Paul Evans Cabinet Image by The Exchange Int

After a four year research project and as part of the exhibit curated by Andrew Blauvelt, Kathryn Goffnett, and Ian Gabriel Cranbrook Museum of Art published a 624-page limited edition book.

The pages feature 200 artists associated with the Academy, 480 images and an expansive look through the archives.

George Nakashima

George Nakashima. Master Woodworker

George Nakashima a sacred relationship with trees

The esteemed American poet Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote In the woods we return to reason and faith One of the most revered names in the American craft movement George Nakashima, must have felt a certain kinship to Emerson's musing. Though most known for his elegant and thought provoking pieces of furniture, Nakashima is also noted for his fundamental belief and philosophy that every tree deserved a second chance at life. From his childhood days walking by the Hoh River Valley to his last years in his workshop and living space in Pennsylvania, Nakashima had always maintained a sacred relationship with trees that have resulted in some of the finest wood furniture of the twentieth century.

George Nakashima was born in Spokane, Washington in 1905 to parents who recently immigrated from Japan. As a young Eagle Scout, he developed an interest in the great outdoors, which led him to take up forestry and architecture at the University of Washington, as well as further studies in architecture at the Institute of Massachusetts. Coinciding with the Great Depression bringing limited opportunities and work experiences in the United States, he left the country and traveled around France, Japan, and India. As a student in Montparnasse, Nakashima was introduced to the city's incomparable architecture and gained lifelong inspiration from Chartres Cathedral and The Pavillon Suisse, a newly designed building by Le Corbusier that featured a purely geometric structure made from natural materials. He moved to Tokyo in 1934 and worked under the architect Antonin Raymond, wherein he appreciated Raymond's style of fusing traditional Japanese elements with innovative Western practices. He was sent to India in 1939 to design and construct one of the country's first reinforced concrete structures. There, he met guru Sri Aurobindo and became a follower of his spiritual teachings. While he did not convert to Hinduism, his time in India led to his modern spiritual belief, wherein he took different aspects from varying religions and made it his own. This newfound spiritual guidance, a harmonious fusion of traditional Eastern and Western elements, would be evident throughout his legacy. As Mira Nakashima wrote in her book Nature, Form & Spirit: The Life and Legacy of George Nakashima: "Sometimes he called himself a Japanese Druid. He also considered himself a Hindu, a Catholic and a hippie, but above all he thought of himself as an intermediary between heaven and earth, joining hands with nature rather than destroying and dominating her."'

Upon his return to the United States, he was struck by how much he disliked the newly constructed American structures and decided to take a break from architecture. After his marriage to Seattle-born Marion Okijama, he was eager to start a new chapter in his life when the attack on Pearl Harbor unfortunately halted his plans. Like all Japanese-Americans at the time, Nakashima's young family, including his 6-week old daughter Mira, were forcibly interned at a relocation camp in Idaho. Tasked with furnishing their barracks to make the space a more pleasant and livable environment, Nakashima met Gentaro Hikigawa, a skilled Japanese carpenter who taught him the craft of traditional Japanese woodworking. A year later, the Nakashima family was released and decided to rebuild their lives and start anew in the aptly-named town of New Hope, Pennsylvania. With a plot of land and the help of family and friends, Nakashima began to build a house and a workshop for his newfound vocation: woodworking.

Providing for his family and starting a new business with limited funds was not an easy feat, yet it is through these circumstances that Nakashima's signature free-edge style would later emerge. As Mira Nakashima recalled in a documentary Collecting George Nakashima If you ever go to a sawmill, they cut off the outsides of the logs because they're crooked and they have knots and holes and cracks…then they get to the inside part of the log and then they can make nice straight-edge lumber This free edge style comprised of irregular edges that were left unfinished in order to show off the natural beauty and contour of each plank. His earliest works in New Hope, however, rarely used the free-edge technique that would later be synonymous with George Nakashima's design aesthetic. Instead he began creating custom-made pieces for his first clients that were free of ornamentation and focused on simple lines to show off the splendor and organic nature of each grain.

After proceeding to produce furniture lines for large-scale retailers such as Knoll and Widdicomb-Mueller, his name became more established and respected as a maker of fine wood furniture. Affluent couples and individuals seeking something different would travel to his workshop and living space in New Hope for private commissions, but Nakashima was mindful of choosing his clients; his pieces could not be made with just the premise of monetary exchange. He found that having a friendly relationship with each client was vital and instrumental to the development of each final piece. It is to this effect that Nakashima knew each and every one of his clients, and the more he resonated with them, the more likely it was that they were given top picks of Nakashima's best selection of lumbers. And these really were the finest choices: whether they were slabs of wood from his own property and local areas or more exotic varieties of Rosewood or English Oak, Nakashima stored and saved piles of logs in his compound of which some are still around today.

In his memoir The Soul of a Tree: A Master Woodworker's Reflections, Nakashima wrote: "There is drama in the opening of a log to uncover for the first time the beauty in the bole, or trunk, of a tree hidden for centuries, waiting to be given this second life." Influenced by the Japanese belief of wabi-sabi, a traditional concept of finding beauty in imperfections, Nakashima took pleasure in finding an ideal use for every part of the tree. While other woodworkers at the time preferred working with the smooth and straight-edged lumber from the inner parts of a tree, Nakashima revered in seeking through the discarded giant roots and pieces with unwanted large cracks. He had an uncanny ability and an almost psychic connection to the wood, sometimes even meditating with each board to find and determine its fullest potential in its second life. As he told Life Magazine in 1970: "I have always been interested in meditation and mysticism. I think I've always been that kind of seeker. But I am also Japanese enough and pragmatic enough to want to give the spirit physical expression."

From a conceptual image in his head, he would draw his design on paper, then he would make a template on the wood board with chalk and pencil. Instead of hiding the large gaps and other anomalies of the wooden plank, he chose to utilize the butterfly joint. Although the butterfly joint was used by others before him, it became a technique that Nakashima really pioneered throughout his life that it began to be called the Nakashima's joint. The butterfly joint was precisely fitted to hold a deep crack in place and would sometimes be made from a different type of wood, unexpectedly creating a focal design element with stunning contrasts in the varying grains. Nakashima never used veneers or any lacquers as the final touch, instead opting to finish each piece with oil to highlight the natural grain of the wood.

Nakashima's most popular pieces range from the sought-after version of the Conoid chair modeled after the flat and curved roof of its eponymous studio, to his highly-regarded free-edge Minguren coffee tables. Yet some of his most celebrated pieces include the large-scale ones commissioned by the late Nelson Rockefeller for his estate in New York during 1973. Considered one of the largest and most important private commissions Nakashima undertook, the lot comprised of over two hundred custom-made pieces. These are most impressive due to their large-scale structures that needed to be proportional to the estate's remarkable size. Another notable commission was for the International Paper Company in 1980, wherein he was tasked to furnish their main headquarters in Manhattan. One-of-a-kind pieces on a scale that pushed his creative boundaries included one of the grandest cabinets he had ever made, as well as very rare pieces incorporating the asa-no-ha pattern, a traditional motif with overlapping hemp leaves that were usually found in sliding screens in wealthy Japanese homes.

In Nakashima's eyes, the tree was always where everything began and it was up to the tree to dictate the form to follow. He merely believed himself to be a skilled woodworker who was able to shape each piece of wood and fashion it into a useful object for human consumption. Perhaps this is why he was often hesitant to put a signature on each of his designs, though some of his later pieces included his signature in black India Ink. Perhaps his reluctance in marking each piece as his own was a sign of respect to the tree; he wanted to let the wood tell its own story and speak for itself. In his essay ‘Meditations on trees and the life of the spirit,' he pondered: "But to leave a piece of wood alone, simply for its own value, is rather Japanese. In Japan, there is a reverence for wood and gentleness towards nature that we don't have here in the West." This recollection of his to Life Magazine further attests to his diverse background of traditional Japanese elements, Western architecture, and mixed spiritual beliefs.

George Nakashima always wanted to be an architect but instead became one of the most successful and renowned woodworkers in the history of American design. Yet he was also an artist, a designer, a father, a husband, and as he declared in an interview in 1985 with National Geographic: "[the] world's original hippie." He believed in world peace and humanitarianism through great design and made that into a reality through the Nakashima Foundation for Peace. In 1984, he was able to purchase a massive 300-year old American Black Walnut log of utmost quality and beauty. A dream that came to him one night led to his vision of using the tree as multiple altars in each continent of the world to unite and bring people together. The first altar site was placed at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine during New Year's Eve in 1986 and was constructed from two of the Black Walnut slabs, ultimately becoming the only alter piece that Nakashima produced in his lifetime.

After George Nakashima's passing in 1990, two more altars were placed in the Russian Academy of Art in 1995 and then at the Auroville Hall of Peace in India. Mira Nakashima took over as the Creative Director of Nakashima Woodworkers and is currently at the helm of her father's business, creating her own designs and pieces that pay tribute to his legacy. She also built the Nakashima Reading Room at the Michener Museum in 1993, a permanent installation that allowed access to her father's timeless furniture and is still used to this day.

George Nakashima's life was full of extraordinary features and ever-present cracks. Like a wood's grain, his life path was often smooth yet full of contrasts, from his beginnings as a Japanese-American with ancestry dating back to Japanese samurais to his transition from an architect to a woodworker. He was at once vehemently opposed to mass production, yet at the same time welcoming new technology and machines. He was against self-marketing and any form of advertising, sticking to his emphasis on creating useful furniture that would turn a dead or dying piece of wood into a fine piece of furniture. Yet after his death, Nakashima's popularity and provenance gradually increased, with the value of his pieces growing exponentially in the last decade.

It can be difficult to imagine a piece of furniture that can look just as home in a modern beach house in Malibu as it can in a private estate in the Catskills, and that's where the genius of a Nakashima piece lies in. A coffee table or a writing desk that is at once attention-grabbing yet harmonious in any space or environment? That's something that only a George Nakashima piece can achieve.